Shan Tattoos: Insights into ink and body art (Part I)

By Naw Liang

(in London, UK and Bonn, Germany)

After another explainable hiatus, I have returned for an overdue entry on the Shan, their culture, history, language and more. But, before dipping into the ink, it is worth reminding everyone that opinions and comments are greatly valued. A recent exchange that arouse from the December posting on “The Shan: Engineering perspectives on and solutions for a 'lost' culture” was one of the most in-depth and thought-provoking discussions that has appeared on All about Shan Studies to date – very inspiring. It is my honest hope that similar exchanges will occur in the future, not only due to my somewhat challenging comments, but also due to expanding access to and interest in Shan issues from Shan and non-Shan enthusiasts and scholars worldwide. I look forward to more of these discussions in the years to come.

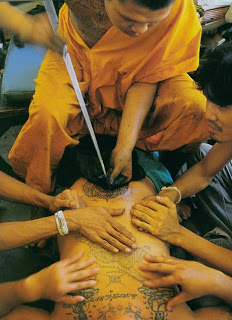

Photo credit: The smoky tattoo photo (above) was originally published by Brent T. Madison in a February article of The Irrawaddy entitled 'Tattoo not Taboo' by David Paquette.

Old sayings speak volumes

In a recent internet article, the old Burmese proverb: “Getting married, building a pagoda and getting a tattoo are the three undertakings that can only be altered afterwards with great difficulty” speaks volumes, not only in Burmese culture, but many Burma-based ethnic minorities as well. Although difficult to apply directly (or, more diligently, implement into daily life, especially in London), the wisdom is inherent, especially if superimposed on modern (the West’s) partner-not-spouse, rent-to-own yet tattoo-happy society. These societal standards of (modern?) Burmese, Shan and other ethnic minorities speak volumes in helping to understand cultural tenets (however historical) as well as distinct societal shifts; it may even, in a very loose and distant way, be a means to compare dissimilar societies, as these societal standards, when tweaked, are not so different from our own historical constructs. Yes, the times may be a-changing, but sayings such as these help provide a clear window to the past. At the very least, they illustrate the generalities, the similarities that span world cultures.

But I am getting off topic while being too general. Double whammy.

It is time to get back on track.

Shan tattoos: a brief introduction

Now, with the statement above firmly in mind, this post will discuss one of the three elements, a cultural act that I have been interested in for some time, both as a researcher and as a promoter/owner: tattoos.

Tattoos (visible, invisible, cartoon, artistic, sentimental, tribal, ethnic, all or none) have skyrocketed in popularity over the last few decades, and they are now a fixture in the public eye through pop culture (mostly music and fashion) and peer promotion. Interstingly, the tattoo boom is not unique to the usual, rebellious or merely fashion-conscious, peer-pressured youth culture in London, New York or Los Angeles (where tattoos may be called tattoos, tats, ink or body art), in Tokyo (called 入墨 or irezumi), in Beijing (纹身 or wénshēn) or elsewhere, but they are starting to show up in growing numbers of young and not-so-young people in more (perceived) conservative societies worldwide, including India, the Middle East and, most pertinent to this site, Burma and the Shan State. Tattoos are sprouting up and gracing places and people like never before. These are interesting body art times.

However, despite the spread of tattooing and the apparent lax reaction to its growth in more conservative locales, Burma and the Shan State have bucked this blanket acceptance of tattoos , particularly of celebrities, musicians and other popular figures, by mounted a pseudo crackdown recently; most vividly, the arrest of a popular musician G-Tone in November 2007, illustrates the official attitude to ink. Although a shame, it iis more distubringly a clear cultural contradiction. After all, tattoos have a long (albeit confusing) history in South East Asia, particularly in the Shan State.

Despite their confusing significance, tattoos can symbolise either an evil deed (such as incarceration) or the pursuit of enlightenment through the sangha (such as joining monkhood). However, Shan tattoos were and (largely) remain reserved to symbolise a rite of passage for boys or spiritual or religious vigour of men, marking a man’s merits and beliefs. It is the rite of passage and the spiritual conviction types of tattoos that I will discuss in this post, while further discussion on prison and gang tattoos and branding in South East Asia will be discussed at a later date.

Regardless of their moralistic value (largely applied by the individual), the roots behind tattooing are spiritual, such as for animist superstitions, based on a belief that ink and body art can protect the body from evil (of course, this ignores the practice of tattoos symbolising previous evil acts. More on that concept/contradiction later).

This association between ink and body art belief deeply links fundamental Buddhist teachings with three core planes of ancient tribal tattooing – these are pain, permanence and the blood (life force) – which mimic a monk’s self-deprivation, devotion and discipline, the powerful three-pronged attack that guides Buddhists in their quest for enlightenment. Additionally, much more than the fashion accessory that some tattoos have become in assorted societies worldwide, tattoos, in this sense, depart from art and gravitate to symbolise an act by dedicated followers to truly bond with their gods, obtain magical powers and, through deep mediation, achieve inner peace.

[Note: I am now officially out of my depth in terms of a comparison between Buddhism and animist tenets and tattoos. Any further clarification or analysis of this linkage would be greatly appreciated. Mai soong kha.]

Shan tattoos: a brief history and explanation

Without digging up the complete history of tattoos – did they originate in Polynesia or ancient China or elsewhere? - ), it is the Shan who are credited with not only importing, but mastering the practice of tattooing in Burma, producing tattoos to ward off evil spirits (animistic), those that recognised devotion to Buddhism (spiritual) or those that symbolise a boy’s journey into manhood.

Of these three types, Shan tattoos (to date) have predominately been used to immortalise a rite of passage for a boy as he becomes a man; they are signs of maturity and virility. The act involved young Shan men who were (and, to a lesser extent, still are) tattooed from the waist to knees by the village medicine man. The act took several weeks and was quite painful: indigo ink or vermillion would be injected under the skin by using a long, often heavy skewer to inscript the tattoo(s), which would be repeated over the period of a few weeks, eventually producing (after several sessions and regular rubbing) a black, then bluish tattoo. The designs mainly consist of animals, the Zodiac and almost invariably include geometric Buddhist patterns (circles, dials, triangles and other). Although often given opium to numb the pain, boys would suffer from the sessions for hours on end, only to have further painful massage sessions to help the ink set. The process was excruciating and lengthy, and it carried a long list of risks, from infections to, in the worst cases, death.

The tattoos: designs and their meanings

A significant aspect of Shan tattoos (and others throughout South East Asia) is the influence of Buddhism on designs and their placement. When choosing a tattoo and where to inscribe it, the village medicine man divides the body into twelve parts, though eight of these predominate: the back, the head and the arms (where illustrations of gods, figures and other sacred mantras, usually in Shan script, are tattooed); and the ears, throat and shoulders (where animals and creatures are reproduced). Additionally, tattoos can be strategically placed, such as those on the chest (popular for soldiers as this is seen as a talisman to protect against bullets) or on other areas in need of protection, such as ankles (to protect against snake bites). Finally, specific designs are often used to symbolise sexual power or stamina (geckos and peacocks); I will let your imagination determine where these might be placed.

[Note: Other methods are also used by the Shan as methods to ward off bad luck or to bring protection. One significant act entails inserting silver or gold discs under the skin to act as a charm, often for those set to go into battle. There is little information available online on this practice, and any suggestions or insights would be appreciated.]

A conclusion of sorts

That is all I have to share at the moment; more study and thought is definitely required. However and as always, I hope that this post, peppered with my incomplete conclusions and shaky linkages, will encourage others to question and challengeg me, nurturing thought, revision and more. Mai soong kha advance.

For now, please see the following links with more in-depth study on Shan tattoos:

Tattoos: Invulnerability and Power in Shan Cosmology by Dr. Nicola Tannenbaum, the only academic article focused on Shan tattooing to date; or More esoterically, please check out Dr. Tannenbaum’s book “Who Can Compete Against the World: Power-Protection and Buddhism in Shan Worldview” which also discusses Shan tattoos, though in a more specific, worldview Buddhist context.

Once again, thanking you for reading and I look forward to your comments.

Mai soong kha,

Colin 'Naw Liang' Savage