By

(in

As promised, this is the second and final section of my limited research on Shan tattoos. And, as before, I would be grateful for any further insights and opinions on this fascinating and core act of Shan culture, both for study and general interest. Your suggestions and comments are appreciated.

Note: Much of the information provided here was found through public sources (academic articles, books and journals and internet research) with additional comments and corrections from events during field visits to eastern Shan State (Mong Yawn, Mongtoon and Mongkok) in 2003 and 2006.

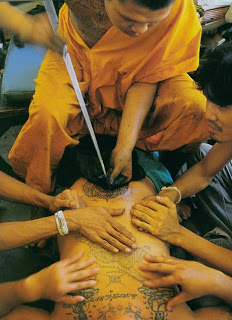

Photo credit: The photo of the monk having his head tattooed (above) was originally published by Brent T. Madison in a February article of The Irrawaddy entitled 'Tattoo not Taboo' by David Paquette.

Shan tattoos: a recap

As mentioned in the March 2008 posting, tattoos are a crucial part of Shan culture, particularly for men, as they are known largely for their spiritual power – they are thought to bring the bearer prosperity; conquer evil spirits; extend one’s life; and even protect against gunshots, knives and other weapons. A tattoo in these circumstances and with this mindset is much more than body art: it is a life force.

The ‘power’ that emanates from Shan tattoos is believed to come from a variety of sources, including the tattoo image; the method by which the tattoo is produced; the tattooist (often called spirit doctor) and the spell that he delivers by blowing on the tattoo and the Shan characters or script, which many believe cannot be read by spirits. However, even during such a spiritually-charged event, a fundamental measurement of the tattoo’s power is the money invested, with the most expensive and difficult tattoos always bringing greater honour, power, position, protection and wisdom.

The professional - the tattooist

The tattooist (or spirit doctor)* was traditionally, though less so in modern times, a travelling herbal medicine man who visited outlying villages during the cool season, usually lodging at monasteries. Spirit doctors chose this time for tattooing especially: the cool season, while traditionally a down-time with little work for the men, providing the ideal opportunity for spiritual pursuits, including tattoos. Furthermore, the cool season was often a time for reflection by many villagers with the temple at the heart of this activity.

* I used tattooist and spirit doctor interchangeably throughout this article.

The place - the mandat**

Although variations exist between the type of structure, the place (within the local Buddhist temple or monastery grounds) where men were tattooed was always the same: a mandat (special structure only erected in the temple grounds) would be set up in an auspicious corner of the monastery, followed by the recitation of sutras and a blessing of the ground with sacred water. The mandat, despite style and size, always follow the same basic structure and are built in the same regimented way. Following the site selection and ritual blessing, the spirit doctor and any assistants would lay down a thick layer of clean and well-watered sand before erecting the cloth roof (which is always fringed with illustrations of the eight planets) and walls, which are constructed from blankets and fenced off by slats of woven bamboo. Next, the fresh and watered sand floor would be covered with banana leaves, mostly to produce a pleasant aroma, before being covered with a blanket. The mandat is then decorated with important articles, including: an image of the

**I do not remember and cannot find whether or not this is a Burmese, Thai or Shan (Tai Yai) word, though I am lead to believe that it is used interchangeably by Shan and

The tool – the needle

The traditional tattooing needle† has three interlocking parts: the head (the heaviest part) that usually resembles a nat (Burmese: spirit) or sacred animal; the middle section (hollow and holding the black or red ink) that makes up the largest part of the tool; and the tip (the ‘needle’ – narrow at both ends and flared in the middle), which may vary in size, but is usually the smallest component of the tool. When completely assembled, the entire needle, which is traditionally made from bronze but can be steel, aluminium or even bamboo (except for the needle), average lengths of 30-37cm (12-15 inches). The tool being used in the photos (right) is longer than most, but not exceedingly. During fieldwork, various sizes were visible, the shortest approximately 25cm (10 inches) and the longest nearing 60cm (24 inches). Although my research is incomplete, discussions with some spirit doctors revealed that longer needles allowed for better control and, as a result, more intricate tattoos.

†I use ‘needle’, though tool or implement might be a better description as the actual needle makes up only the tip of the implement.

The medium – the ink

The ink∫ is made from the soot of crude, peanut or sesame oil and lard that is collected from lamps and mixed with dried fish gall bladder before being tied up in a cloth to ‘ferment’. The soot is then mixed with a handful of leaves of boiled, bitter gourd in a large pot and boiled again. Next, the soot is removed and dried. In the final stage and just before use, the dried soot is mixed with boiled water or pure oil to form a thick paste. The ink is now ready for use, though some minor alterations, including mixing in limejuice and special herbs, can also be undertaken before the ink is applied in the tattooing process.

∫Traditionally, black ink was the only colour used for tattooing. Although my information is conflicting, the vast majority of tattoos are still produced in black ink only. However, I have heard that tattoos are increasingly using two colours: black ink, which is used for astrological drawings, red ink, which is used for religious purposes. If a red tattoo or red ink is selected, the spirit doctors will offer the nat coconuts, bananas and rice.

The task – tattooing

Now, the recipient of the tattoo enters the mandat (via the appropriate door), meets the spirit doctor and selects a tattoo. Although some friends and family are allowed to gather nearby to listen to the process, no one‡ is allowed into the mandat to watch, however, it is common for a young assistant to work with the spirit doctor, ferrying messages back and forth about the process’ progress to family and friends

‡ The only ones allowed to witness the tattooing were four close friends selected to hold the recipient of the tattoo down if required.

Before the actual tattooing begins, the recipient of the tattoo prays to

Initially, the selected designs are marked on the skin with design blocks that have been cut and coated with sooty ink to create templates. Next, the outlines of the tattoo are etched into the skin, with leaves crushed and rubbed into the cuts afterwards, making the black ink turn a greenish black hue, which is considered more beautiful that pure black. If a traditional Shan waist-to-knee tattoo was selected, the spirit doctor would start at the waist, work around it, before proceeding downwards, tattooing one thigh at a time. Depending on the skill of the tattooist, one thigh, from waist to knee, would usually take about five hours; the tattooing starting at dawn to avoid the afternoon heat. The second thigh would not be done until later, often after consulting the recipient, though it is rare for anyone to have both thigh tattoos completed in less than a week. After the new tattoos were completed, assistants would wash the tattooed area with boiled water and herbs, to be repeated everyday by the tattooed person and/or family members, to ward off infection and aid healing. When everything was completed, the newly tattooed person would leave the hut and clap three times, a traditional Shan (and Burmese) display of manliness.

For more information, please visit the Sure Hope site (here) on Shan and animism or two independent traveller sites - Cameron in Sea or NineMSN.

Once again, thank you for visiting and mai soong kha.

Naw Liang